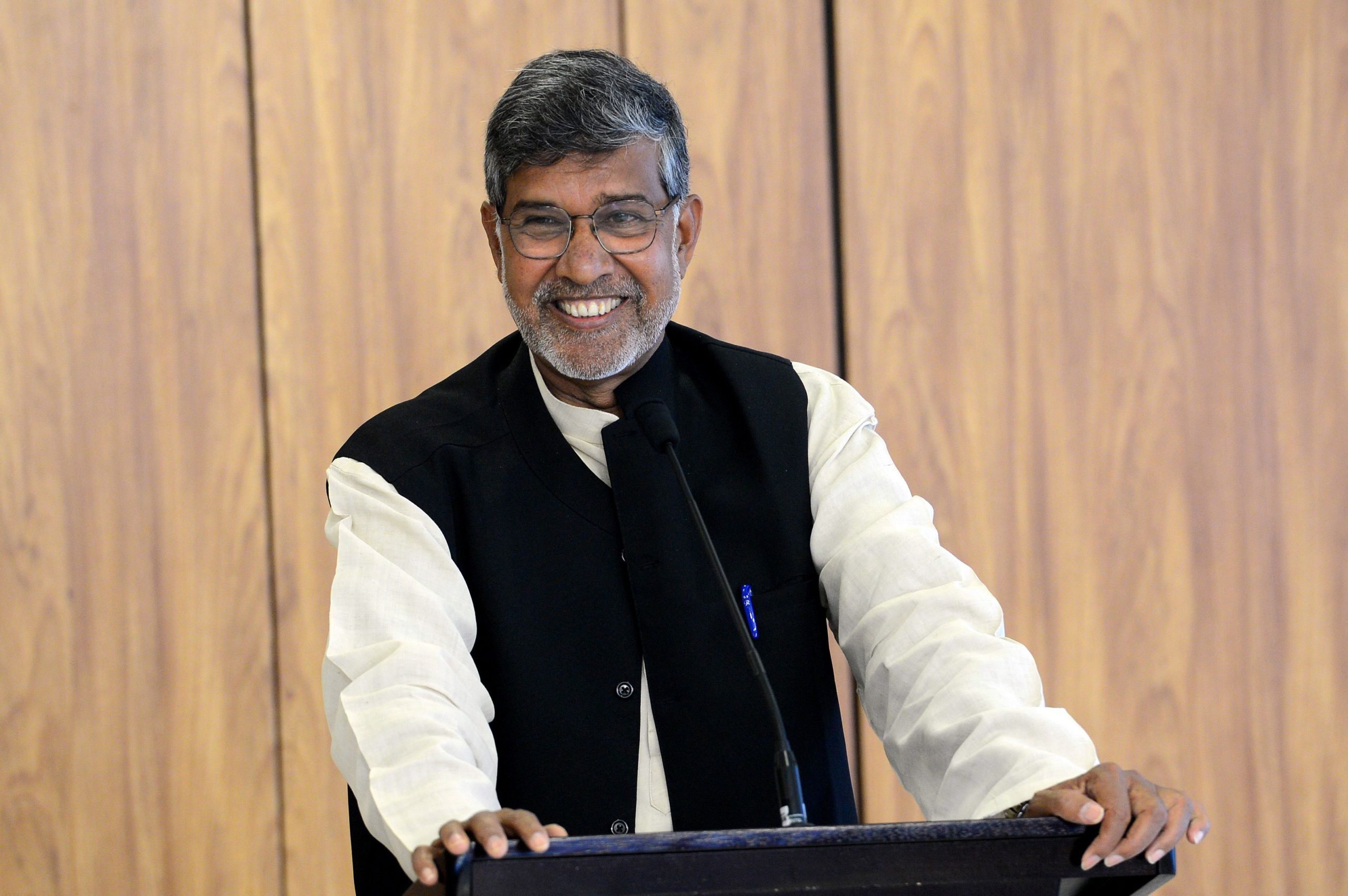

On the occasion of the World Day Against Child Labour, Give speaks to child rights activist and Nobel laureate Dr Kailash Satyarthi on the fight against child labour in India and the world.

Give India: Soon after you won the Nobel Prize in 2014, you said, “We can end child labour in our lifetime.” Seven years down the line, do you feel that the goal can be achieved?

Dr Kailash Satyarthi: I am a man of optimism and I believe in the power of change. I believe this is the century of transformation. Thirty-five years ago, nobody accepted that children were still being enslaved and exploited. But we have changed the course of history by transforming ignorance to knowledge, intent to commitment and obligation to act.

The Global March Against Child Labour that I initiated in 1998, where I embarked upon a journey of 80,000 km around five continents with former victims of child exploitation, is a testimony of the world moving forward from ignorance to knowledge. We demanded an international law against child labour (ILO Convention 182 on Worst Forms of Child Labour) which was adopted unanimously in 1999. During the culmination of Global March, I had also called for a day dedicated to raising awareness on the issue, which today is celebrated as the World Day Against Child Labour on 12 June.

Since the adoption of this Convention, countries around the world began passing national laws and action plans and allocating budgets, which were non-existent before. World Day Against Child Labour is also observed across the world today. After 22 years, this Convention is universally ratified showing the commitment of the world that it is now ready to end employment of children.

Given that the entire world is with me on my call to restore children’s rights, and if the leaders and the society are driven by compassion and not greed, I truly believe that I can see an end to child labour in my lifetime.

GI: How widespread is the problem of children in India being put to work? Have the numbers been coming down in recent decades?

KS: Child labour is a grave and rampant issue in India. As per the Census 2011, there are 10.1 million children were put to work (5.6 million are boys and 4.5 million are girls) but I believe this is an underestimated number, and now with the pandemic pushing thousands of children out of school, it is likely to rise.

We often come across children working on the streets, in shops and eateries, and at homes. But some children remain invisible. They work in the farms and fields, in factories and workshops, and also in brothels. In 2002, the first global report that came out on child labour estimated 246 million children were victims. From 2002 to 2016 the numbers came down to 152 million. However, as per the ILO’s recent estimates, 160 million children are now in employment.

This means that even though the number of countries adopting international laws and creating national policies saw a rise, their ineffective implementation has hampered the progress.

GI: What have been some impediments in India that we could not end child labour despite the right laws, and activists like you?

KS: After consistent and sustained advocacy on the creation of laws against child labour, my first victory came when the Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Act of 1986 was adopted even though it was a flawed law. However, I continued with my fight by continuously engaging with the MPs, leaders, mobilising voices and empowering children in child labour to voice their concerns on all the platforms.

I also continued working on the grassroots and internationally raised the agenda of child labour on world platforms as well as in countries in Asia, Africa and Latin America. Amidst all this in 2014, I was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

Soon after India also ratified the ILO Convention 138 on Minimum Age For Admission to Employment, leading to the amendment of 2016 in the CLPR Act which now aligns the right to education till the age of 14 with the prohibition age of child labour. Even though it is a big victory for us, the amended law still allows for children above the age of 15 to work in family enterprises.

So, this means that we do not have the “right laws” despite efforts made by me and many other comrades in this journey. A “right law” is one when a child, who is defined as a person under the age of 18, can fulfil its potential by enjoying his or her right to education, health and safety and enjoy his or her childhood.

GI: A Nobel laureate like you can have a wider reach to address the issue. But what is your advice to those social workers and organizations that are tirelessly working in the field to fight child labour?

KS: There is a saying that ‘no one can change the world, but one can change the world of one person.’ And that’s all it takes to make a difference. There are several amazing social workers and organisations who are working hand-in-hand for the cause of ending child labour. These people and organisations are our real assets. They are changing society. These are our frontline warriors who work day and night to ensure that every child goes to school, rescue children from child labour and trafficking.

My organisations, Kailash Satyarthi Children’s Foundation, Bachpan Bachao Andolan and Global March Against Child Labour are with grassroots organisations and social workers to bring that real-ground level change from the community to district and national and international level.

For such ground-level organisations and people, there is only one piece of advice. Continue influencing and inspiring positive change in at least one person’s life – be it an adult or a child. Everyone needs to do their bit in our struggle for children’s rights.

GI: There are several international agreements on child labour, and initiatives like RugMark and others have helped a great deal in bringing down child labour in large industries. In your opinion, what more can be done?

KS: The carpet which was back then the region’s most expensive exporting item was an industry filled with child labourers who stitched carpet looms with their nimble hands. At that time, people were scared to enter this industry run by the carpet mafia. But Rugmark, now known as Goodweave, emerged as a path-breaking initiative that gave rise to an increased demand for child labour free carpets.

Apart from this, the Global Campaign for Education (GCE), where I served as the founding President, was one of the first initiatives where we established the link between education and child labour. GCE, which till today is the largest coalition on education for marginalised children, went on to advocate for greater rights of children in child labour and other vulnerable children to receive a quality, inclusive and fair education.

One needs to innovate and come up with newer and fresh ideas to fight for what is ours — our human rights and the right of every child to go to school, receive meaningful quality education and health. Youth of this world is my hope in this regard. They have all the potential and innovation to create many more “firsts” that will change the narrative around human rights.

GI: Which are some sectors of concern that continue to employ child labour in large numbers?

KS: They are mostly in the unorganised/informal sector. Agriculture is said to have the highest number of children in child labour. Children can be found working in cocoa, coffee and sugarcane plantations, fisheries, brick kilns, garment factories, mining, domestic service, etc.

GI: Looking back, has the Nobel Prize changed you in any way?

KS: The Nobel Prize has indeed changed me, but for the better. It has brought in a heightened sense of responsibility on my shoulders to keep the fight against child labour on, and to inspire more actions around the world for this cause.

While I remain the same person, whom the children we rescue and the associates of my organisation, fondly call “Bhaisaab,” I continue to change and adapt my outlook with the changing world, to keep up with the times and also continue aligning my thought process and plan of action with the need of the hour, with only one agenda — to see an end to child labour in my lifetime.

To support Kailash Satyarthi Children’s Foundation, you can donate here.

Interviewed by V. Kumara Swamy

–

Give’s mission is to “make giving bigger and better.” Give is the most trusted donation platform in India for fundraisers and crowdfunding campaigns. Through our technology solutions, we enable individuals and organisations to fundraise and donate to a cause, charity or NGO with trust and convenience. Give’s community of 2.7M+ individual donors and 300+ organisations supports 3,000+ verified nonprofits with 80G deduction and serves 15M+ people across India. Find a fundraiser today!

Discover more from

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.